Mrs Chippy,

of Shackleton's Endurance Expedition

(Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition)

Left-click thumbnails for enlargements (JavaScript should be enabled),

but please allow all images to load before doing so, or some may not display

(if this happens, use Refresh from your toolbar to reload the page)

Mrs Chippy was the tabby cat that accompanied Ernest Shackleton and his crew on board the Endurance when they set sail from the East India Docks in London on 1 August 1914, bound for the Antarctic, initially South Georgia. In spite of the name he was a tough tomcat from Glasgow, and he belonged to Henry (Harry) McNish, ship's carpenter and master shipwright. While preparing for the trip McNish found the cat curled up in one of his toolboxes, as though determined to be included, and that was what made his master decide — having earlier been unsure whether or not to take him — that a cat would be a good companion on the voyage and that he should go along.

Shackleton was pleased to have the cat join the crew, as a good mouser was important on board ship to keep rodents under control and prevent them damaging the stores (as of course the crew of Amethyst would later confirm: see the story of Simon and HMS Amethyst). It is said that when master and cat came on board, Mrs Chippy followed McNish around like an overpossessive wife, and that's how he acquired his name — which stuck even when they found out he was in fact a tomcat! He was a handsome, intelligent, good-natured and affectionate animal, and a first-rate mouser and ratcatcher to boot. He soon established himself and became a favourite with most of the crew. (For anyone unfamiliar with the term, I should explain that 'chippy' is a colloquial and somewhat affectionate name in Britain for a carpenter.)

Shackleton was pleased to have the cat join the crew, as a good mouser was important on board ship to keep rodents under control and prevent them damaging the stores (as of course the crew of Amethyst would later confirm: see the story of Simon and HMS Amethyst). It is said that when master and cat came on board, Mrs Chippy followed McNish around like an overpossessive wife, and that's how he acquired his name — which stuck even when they found out he was in fact a tomcat! He was a handsome, intelligent, good-natured and affectionate animal, and a first-rate mouser and ratcatcher to boot. He soon established himself and became a favourite with most of the crew. (For anyone unfamiliar with the term, I should explain that 'chippy' is a colloquial and somewhat affectionate name in Britain for a carpenter.)

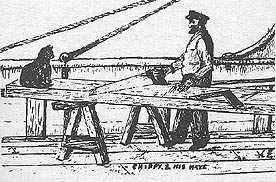

Mrs Chippy's new friend

Mrs Chippy's new friend

At one of the ports of call, Buenos Aires, a 19-year-old British man stowed away on Endurance, with the aid of a couple of his friends who had been legitimately signed on. Named Perce Blackborow, he was not discovered until three days later when the ship was well under way; after giving him a dressing-down in front of the crew, Shackleton let him stay for the duration of the voyage and put him to work. He was willing and proved to be an asset, eventually gaining promotion to steward. It was Blackborow who became Mrs Chippy's champion and second-best mate, and what seems to be the only existing photograph of the cat is on the young man's shoulder. It was taken by expedition photographer Frank Hurley and looks as though it might have been taken outside the galley.

There was one crisis during the journey south, when Mrs Chippy seems to have decided the whole thing was a mistake, and made a jump for freedom out of a cabin porthole, straight into the cold and inky-black waters of the South Atlantic. Fortunately it was a quiet and calm night and the officer of the watch, Lt Hubert Hudson, heard the cat's cries and was able to smartly turn the ship around to pick him up. He was in the freezing water for ten minutes or more, but soon recovered — although undoubtedly one of his nine lives had been used up! The incident is recorded in the diary of Thomas Orde-Lees, 13 September 1914 (in which he refers to the cat as 'she').

Annoying the dogs

Being an equitable cat, there wasn't much that bothered Mrs Chippy and he settled down to find the warmest and most comfortable places on board, accept titbits from the crew in exchange for a purr, and do his job of protecting the provisions. What he did not like were the 70-odd Canadian sledge dogs that lived a rather miserable life chained up in lines of restrictive kennels on each side of the deck. These dogs suffered from lack of exercise and — oddly, considering the important role they would be expected to play later — were not very well looked after; indeed, poor condition led to the early demise of several of them. Not unexpectedly they howled and made a lot of noise, and this rather unnerved the cat at first.

However, as time went on he gained in confidence and would prowl around on top of their kennels mewing; then sharpen his claws on the roofs (the mainmast was also a favourite claw-sharpening spot), and sit there calmly washing himself. Needless to say, these actions did not endear him to the dogs, which would be driven into a hysterical frenzy.

Trapped in the ice

Circumstances were to change, though, as in mid-January 1915 Endurance became trapped in frozen pack ice from which, despite the best efforts of the crew, she would never escape and which would eventually crush her. Becoming apparently rather bored with the proceedings at one stage, Mrs Chippy seems to have decided the best thing to do would be to hibernate for a while, and he disappeared to somewhere warm and quiet from the 5th to the 10th of February. The crew were distraught, thinking he had gone out onto the ice and frozen to death, and were greatly relieved when he reappeared. No doubt he had some extra 'treats' to eat, as a relief from the usual fare of sealmeat for breakfast, sealmeat for lunch and sealmeat for supper.

After about a month, when the Antarctic winter was setting in and it was obvious the ship was not going to be on the move anytime soon, the dogs were moved off the deck into specially built houses made from ice blocks, on the ice floe beside the ship. These were called 'dogloos'. The dogs also had a stout wire between posts along which they could run for exercise while remaining securely chained to it; again Mrs Chippy would tempt fate by watching them from just out of range. One day the bo'sun John Vincent, an unpopular man but who quite liked dogs, accused the cat of unnecessarily provoking them. He picked him up roughly by the scruff of the neck and threatened to throw him to the dogs. Blackborow rescued the cat before the threat could be carried out — but that was another life gone! A formal complaint was made against Vincent, who was in fact demoted as a result.

In general Mrs Chippy did not like the ice, which became lodged between his toes and pads, and spent most of his time below decks, with occasional outings to check on the crew's activities and see how they were getting on. During July, along with the rest of the crew, he was weighed, and at 9lb 10oz (nearly 4.4kg) was considerably heavier and stockier than at the start of the voyage (unlike the rest of the crew, who had all lost weight, although they were healthy). The cat spent a lot of time grooming and the diet — now changed to pemmican — seemed to suit him. However, he drew the line at penguin meat and refused to touch it.

By October 1915 winter had begun to loosen its grip, and at one time hopes were high and it seemed as though Endurance might be able to gain her freedom from the ice and continue her voyage. But by the end of the month it was obvious it was not to be, and the ship was beginning to break up under the pressure of the ice. Mrs Chippy continued to sleep through much of what was happening, prompting the remark, years later, from a crew member: 'Mrs Chippy's almost total disregard for the diabolical forces at work on the ship was more than remarkable — it was inspirational. Such perfect courage is, alas, not to be found in our modern age.'

Shackleton's plan

Towards the end the crew had to camp out on the ice in tents, while Shackleton planned what to do for the best. He eventually decided they would have to head for the nearest land, nearly 350 miles away. In order to have any chance of success, he told the men they would have to be quite ruthless in taking with them only what was absolutely essential — which would mean there would be no place for Mrs Chippy. Nor, indeed, ultimately for the dogs, who despite being rationed were consuming more meat than the men. His crew were entirely loyal to Shackleton and respected his judgement, and so the decision had to be made.

When the time came the biologist, Robert Clark, picked up Mrs Chippy and gave him an affectionate hug and stroke. Crew members paid their respects with a caress, a stroke or a tickle under the chin; the cat had been their companion throughout all their adversity and a great source of comfort in their numerous hardships. Mrs Chippy, of course, loved all the attention and treated it as his due.

Mrs Chippy's demise

Authors tended not to dwell upon the final playing out of the sad tale. It seems that after the crew had made their farewells McNish probably took the cat into his tent to say his goodbyes, when the steward Blackborow somehow rustled up a bowl of sardines — Mrs Chippy's favourite and a real treat. He ate them with obvious pleasure, then washed and stretched out for a good sleep, little knowing it was to be a never-ending one. It is possible that the sardines were laced with a sleep-inducing drug. Blackborow returned once to embrace the cat tightly, telling him how glad he was that they had been shipmates, and then left.

In his book South, published in 1919, Shackleton himself states that on the afternoon of 29 October 1915 the cat and some of the puppies were to be shot. The following day Hurley wrote in his diary, 'Sally's 4 pups, Sue's Sirius and McNish's cat, Mrs Chippy shot at 2:55 p.m.' It seems the task was undertaken by Frank Wild, Shackleton's second-in-command. (Five dog teams were subsequently destroyed in the same manner in January 1916, and the remaining two in March.) McNish had little time to mourn his beloved cat, as he had much work to do preparing and modifying the three lifeboats for sea; the lives of all the men would depend on these boats. But from that time on the carpenter had a growing resentment for Shackleton, and as their escape expedition went on it became harder and harder for the leader to control him. One result was that Shackleton did not recommend McNish for the award of a Polar Medal, despite the vital part his carpentry skills had played in ensuring the survival of the lifeboats — and thus the men's lives — in some of the most hostile seas in the world.

The upshot, as is well known, was that eventually, after three and a half months and against great odds, Shackleton did manage to lead all the crew to safety and no human life was lost. There are plenty of accounts of their adventures and I shall not repeat them here. But NcNish never forgave Shackleton for having his cat shot.

The carpenter – and a tribute to his cat

There is a postscript to the story of the unfortunate Mrs Chippy. In 1925 McNish went to Wellington, New Zealand, where he worked on the waterfront until he was injured. He survived there until 1930, destitute, with help from the waterfront folk. The curator of Antarctic History at the museum in Canterbury, Baden Norris, recalls being taken as a young boy to see McNish when he was old and ill; even then he was still mourning the loss of his cat. 'The only thing I remember him saying,' says Norris, 'was that Shackleton shot his cat.'

But to the seamen of Endurance, the carpenter was a hero. When he died a naval funeral was arranged, with bearers from the Royal Navy and a gun carriage supplied by the New Zealand Army. But his grave, in Karori Cemetery, Wellington, was unmarked until 1959 when the NZ Antarctic Society raised a headstone. In June 2004 the society cleaned up the grave and commissioned a life-sized bronze sculpture of McNish's beloved cat to adorn it. The sculptor, Chris Elliott, tried to represent the cat as alert, but with his body relaxed as though he were lying on his master's bunk. Chris very kindly sent us some photos (below) of the sculpture being admired by visitors, together with one taken beforehand in the bronze-caster's yard (centre) and one in its final position on Henry McNish's grave (second from right). Further examples of Chris Elliott's work can be seen at his website.

McNish's grandson Tom, who lives in England, was delighted and felt his grandfather would have been pleased. 'I think the cat was more important to him than the Polar Medal,' he said.

In 2006 a fine plaque dedicated to Harry 'Chippy' McNish was unveiled at the library in his Scottish birthplace of Port Glasgow. In 1958 the British Antarctic Survey named a small island off South Georgia in his honour: McNeish Island. McNish's surname was and is commonly spelled 'McNeish' — Shackleton himself used it — but his birth certificate revealed it to be McNish, and in 1998 the name of the island was accordingly officially altered. His gravestone, however, uses the McNeish spelling.

Book choice . . . and a stamp

Finally I must highly recommend the marvellous book Mrs Chippy's Last Expedition, by Caroline Alexander (1997, Bloomsbury Publishing, ISBN 07475 3819 0). It's written as a diary kept by the cat, starting in January 1915 and ending with the meal of sardines. It's an amusing, poignant and fascinating read, and there are many interesting photographs of Endurance and her crew during the voyage. It's a pity that on none of them is Mrs Chippy to be seen; he always seemed to manage to be just out of shot!

However, played by 'Mac', Mrs Chippy did feature in the 2002 Channel 4 film Shackleton, starring Kenneth Branagh in the title role and with Ken Drury playing McNish (available on DVD).

In February 2011 the well-known photo of Mrs Chippy with his friend Perce was featured on a postage stamp. A set of six stamps showing various domesticated animals (and a penguin) that had been to the Antarctic was issued by South Georgia & the South Sandwich Islands, and the cat is on the top (£1-15) value. For an image see our April 2011 stamp review.

Links and further reading

Mrs Chippy was not the only cat to have taken part in polar exploration.

See our companion article describing some other Antarctic Cats

and for a modern twist to Mrs Chippy's story see Post-war Antarctic Cats.

A musical journey

Frank Bossert is a German musician, composer and songwriter living in the north of the country. For some years he has worked on independent musical projects, producing and releasing CDs particularly in the Celtic genre, and highlights from his albums can be found on major-label compilations next to songs by the likes of Clannad, Enya and Mike Oldfield.

In 2001 Frank heard for the first time about Sir Ernest Shackleton and the Endurance expedition, and conceived the idea of making a modern musical composition inspired by the expedition's amazing story. The album is now available as Shackleton's Voyage, a 51-minute musical interpretation telling the sensational story of the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition of 1914-1916 in a series of 15 tracks. The atmospheric music is themed around the various phases of the expedition and the stages of the men's survival. Artwork and an accompanying booklet feature original photographs taken by expedition photographer Frank Hurley and licensed by the RGS in London and the SPRI in Cambridge. There was originally a track entitled Mrs Chippy's Dance, but the title was later changed because of a lack of suitable photographic material to accompany it.

The CD is available worldwide by ordering from the website, where more information can also be found, and also from other sources such as Amazon. Further details of the album and the whole project can be seen at MySpace.

![]()